| June 18, 2011 NYQS at Three Jewels

Present:

Members:

Stephen Dydo

Matthew Flannery

Bo Lawergren

Tomoko Sugawara

Marilyn Wong-Gleysteen

Other Visitors:

About 10 other people came.

This was our second meeting at the Three Jewels Community Center, a loft near Union

Square which has programs focusing on Tibetan Buddhism, meditation and yoga. The

evening was a relaxed concert event. There were presentations by Stephen, Marilyn,

Bo and Tomoko.

Before the program opened, two scrolls of calligraphy were hung amid the meditation scrolls in meditation room:

1) 搏琴 a scroll written by Yuan Jung Ping

袁中平

for Matthew Flannery

2) A scroll by Yi Bingshou 伊秉綬 , part of a couplet (a second nail was unobtainable to hang both parts) belonging to Marilyn Gleysteen.

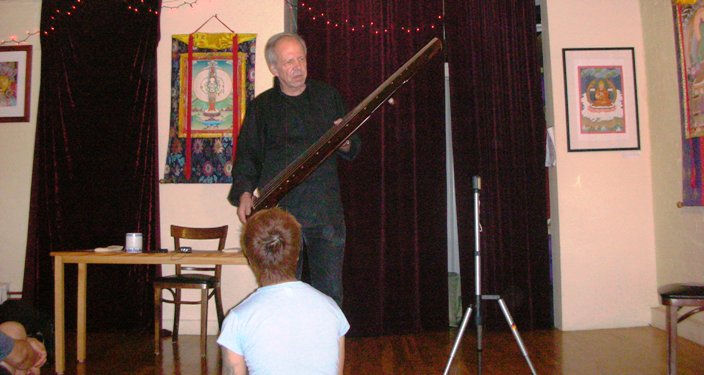

Stephen showing parts of a qin. This

is a modern instrument by Wang Peng, which uses traditional silk strings. This

is the same instrument played by Marilyn and Stephen in the program.

The program opened with NYQS President Stephen Dydo 戴德

welcoming our audience. Stephen gave a brief history of the qin,

its place in Chinese culture, the instrument's construction, and the use of silk strings, almost exclusively by NYQS members.

A question was asked about the use of metal strings, to which came the reply that it had a harsher sound, was easier to tune,

and was used primarily during the Cultural Revolution when silk strings became difficult to obtain.

He then performed the following pieces, to which he provides the notes:

平沙落雁 Pingsha Luo Yan (Geese Alighting on a Sandy Beach)

This piece exists in more versions than any other in the qin repertoire, appearing in more than 50 books. This is despite the

fact that the earliest version we have made its appearance relatively late, in 1634. (According to tradition, the melody dates

back to the 8th or 9th century.) Every qin school has its own version, with differing degrees of ornament; but all that I have heard

are recognizably the same melody. Marilyn has written of it: "Wild geese are free-spirited subjects of painting, poetry and music:

their soaring and gliding are symbols of a learned and searching mind. This piece is a classic of qin repertory, its musical language

evoking the primal sounds, movements and energy of these remarkable birds and their connection with water and air."

秋塞吟

Qiu Sai Yin (Song of Autumn beyond the Frontier)

This piece is related to (some books say "the same as") two other qin pieces, Shuixian Cao ("Water Spirit Melody") and Saoshou Wen Tian ("Scratching Head, Question Heaven").

Qiu Sai Yin is said to describe the desolation of Wang Zhaojun, a Han dynasty court lady sent beyond the northern frontier as a peace offering to a barbarian chief.

She has been associated with the pipa (a lute-like instrument imported from the Middle East) since the Tang dynasty. However, another, more qin-related story concerns

the ancient qin virtuoso Bo Ya who, having reached a certain high standard, was taken by his teacher Cheng Lian in a boat to meet his teacher on a deserted island.

After communing with nature in solitude for a week, Bo Ya was picked up by Cheng Lian in the boat. Cheng Lian asked if Bo Ya if he had met the teacher, and Bo Ya said,

"Yes."

To listen Stephen's opening talk, please click here.

To listen Stephen's playing of Pingsha Luo Yan, please click here

.

To listen Stephen's playing of Qiu Sai Yin, please click here

.

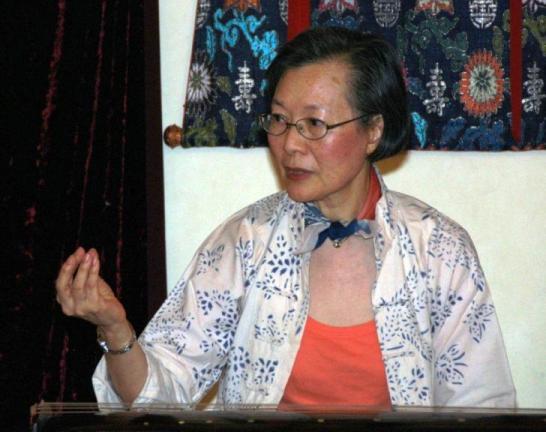

Marilyn Wong Gleysteen

Marilyn Wong Gleysteen 王妙蓮

then spoke. First she introduced

the scroll Matthew brought, saying that NYQS was founded eleven years ago by

Yuan Jung-ping, and even though he is not attending our meeting, he is present

in the form of his superb calligraphy, Bo Qin 搏琴

"Striking the Qin." She

then introduced the officers present, and mentioned that among our 20 NYQS

members, two are harpists, and that today's performance would be of both guqin

and angular harp. It is important to remember that the word "Qin" is

the generic term for any stringed instrument, as far back as Confucius' time.

Marilyn then talked about the couplet by Yi Bingshou 伊秉綬

(1754-1815) , summarizing the

meaning as saying how in the presence of learned persons, there is a flowering

of talent, and that human beings become immortal through their artistic gifts

to others. She also mentioned how she first met Jung-ping at the China

Institute exhibition on Qin culture in 1999, the founding of NYQS in 2000, the

visit to the Freer-Sackler Gallery to see the exhibition of the Music of

Confucius, to which catalogue

Bo Lawergren

had contributed a major essay, and other early meetings covering topics of

Chinese painting and calligraphy. She also passed around some early

Journals of the NYQS which has ceased publication since a website has been

established.

Marilyn then performed two pieces, prefacing by saying that since JP left NY

in 2004, she had not had proper lessons and had acquired some bad habits in

her technique. In the last two years, she has tried to improve her technique

by starting qin lessons with Sou Sitai 蘇思棣,

a master who studied with Mme Cai Deyun 蔡德允

(died 2007). After a few comments

about the basics of qin technique, -- the open string, harmonic and stopped

string sounds and the range of finger positions to create different musical

effects -- Marilyn played the following tunes; the notes are by John Thompson:

Guqin

Yin 古琴吟

(Old Qin Melody)

Liangxiao Yin 良宵引(Peaceful Evening Prelude)

Liangxiao

Yin

has been a very popular melody, occurring in over 30 handbooks from 1614 to

1914;4 two of these versions have lyrics. The melody has long been considered

as a beginners' melody, and it remains very popular as such. At the same time

it is a good example of how a melody can appear to be very simple, and yet

playing in a way that brings out all its color and subtlety is a great

challenge to a player's technique. (Notes by John Thompson, http://www.silkqin.com/02qnpu/36sxgq/sx15lxy.htm)

To listen Marilyn's playing of Guqin Yin, please click here.

To listen Marilyn's playing of Liangxiao Yin, please click here

.

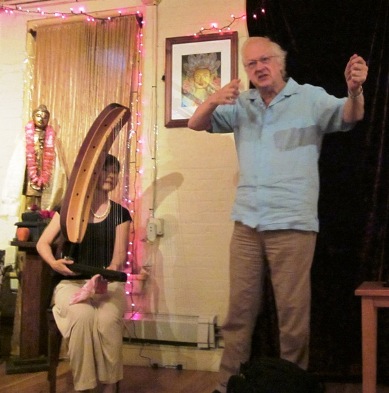

Tomoko and Bo explaining the kugo

Tomoko

Sugawara 菅原朋子brought her angular harp 箜篌

(konghou or kugo) and

Bo Lawergren

then spoke about their recent work and a timely article written by Bo,

"The Rebirth of the Angular Harp," published in Early Music:

America (Vol. 17:2, summer 2011) featuring Tomoko, who is among the

world's leading specialists performing on the kugo, and Bo a renown emeritus

scholar of archeological musical instruments. Bo first gave a brief history of

the harp:

“The

modern European frame harps that we're all familiar with now did not appear

until about 800 CE (Christian era). What happened before that? The arched harp

emerged around 3000 BC in Mesopotamia and Iran and a few centuries later in Egypt.

Meanwhile, back in Iraq/Iran the arched harp gave way to the angular harp

around 2000 BC, lasting nearly 4,000 years. It traveled on the Silk Road and

reached China by 550 CE. A few centuries later it reached Korea and Japan.

There are many detailed pictures of ancient harps, found in archaeological

digs. Since the first millennia what was known about the angular harp, the

first type of harp invented about 1900 B.C., came

mainly from pictures and archaeology. Eventually texts appeared and from

around 1000 A.D. we know even tunes played on this instrument. This ancient

angular harp is called kugo in Japan, chang in Iran, and trigonon in Greece."

To listen to Bo's introduction, please click here.

Tomoko and her

kugo

Tomoko then

performed the following pieces (notes by Tomoko):

Archaic

Phrase by Kikuko Masumoto

(増本伎共子)

In Archaic Phrase

for Kugo the eminent Japanese composer Kikuko Masumoto uses several short

melodic kernels taken from Gagaku, a type of Japanese court music that emerged

at the end of the first millennium CE and still is played today. Wind and

percussion instruments dominate the court orchestra while strings are few and

play only intermittently. Their phrases are short and quick, seemingly at

odds with the slow and steady flow of tunes on the wind instruments. Ms.

Masumoto focuses on the ancient phrases which, without their usual context of

winds, shine in stark beauty. The piece was composed in 2007 and is

dedicated to Ms. Sugawara.

Gulpembe

Sephardic Song (arr. Tomoko Sugawara)

To listen to Tomoko's playing of Archaic Phrase, please click here.

To listen to Tomoko's playing of Gulpembe, please click here

.

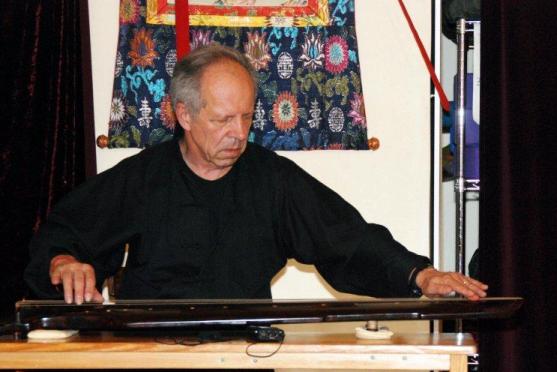

Stephen playing Meihua San Nong

Then Stephen closed the program by performing the last of

his pieces,

梅花三弄

Meihua San Nong (Three Variations on

Plum Blossoms). About this piece, Stephen says: The story of this piece goes back to the 4th century. It

mentions two literati, Wang Ziyou and Huan Yi, a famous musician. Meeting by

chance while travelling, both got off their carts to talk to each other. Wang

said that he had heard that Huan was an excellent dizi (bamboo flute) player,

and asked him to play a piece. Huan responded by taking out a flute and playing

the melody Meihua (Plum Blossoms). This was later adapted for the qin,

with the flute melody repeated three times in harmonics.

The symbolism of the plum blossom is of strength in the face of adversity. It

appears while snow is still on the ground, before those of any other tree. Thus,

it fears neither snow nor bitter cold. This early version, transmitted from Wu

Zhaoji, is a bit shorter and simpler than later, more embellished scores.

To listen to Stephen's playing of Meihua San Nong, please click here.

The performance ended at approximately 9:15 pm.

|