| |

Main Menu

Main Menu

選 項

Year 2000

Year 2001

Year 2002

Year 2003

| |

" Music in the Age of Confucius, "

an Exhibit of Ancient Instruments at the

Sackler Gallery (cont.)

|

|

Ten-stringed qin-zither and replica tuning pegs, from the tomb of

Marquis Yi of Zeng, Leigudun, Suizhou, Hubei Province. Fifth

century B.C. Carved lacquered wood. Length 67 cm, width 19

cm, depth 11.4 cm. Hubei Provincial Museum.

Photograph by John Tsantes.

|

|

|

View of qin with top and bottom separated and replica tuning

pegs in place.

Photograph by John Tsantes

|

|

Buried among this unique profusion of instruments

and their stands and storage boxes lay one small qin.

Quite small. Scarcely more than half the length of the

modem qin, this instrument is one of three early qin to

have been unearthed in modem times. So different are

they from the modem qin that they appear at face to be

a different instrument, and it has taken some analysis to

establish that old and new forms are relatives. The old

qin (a ku qin, literally) bears more overt resemblance to

a hand-held instrument like a violin or guitar than to a

zither, with a short, rectangular body, whose long sides

are indented in straight lines like the outline of a

geometric figure eight, and a wide, flat neck. Baffling

is the bottom, which matches in outline, but is not

attached to, the top. Absent from the catalog is much

backroom debate as to the position in which this

instrument was played and the role of its independent

bottom plate, which curator Jenny So and Bo

Lawergren outlined during the tour. The instrument has

a single anchor pin for the strings under the neck on the

left end and tuning pins for ten strings inside the body

on the right. These are the earliest extant examples of

tuning pins for any instrument, and, unlike today, they

were turned with a key.

Bo Lawergren wrote "Strings," the third chapter of

the exhibition catalog. Here, he summarizes

information on the three types of zither found in the

marquis' tomb (se, zhu, and qin) and also provides

information on the fourth zither popular in early times,

the zheng. The catalog is an excellent summary of the

state of knowledge on most of the instruments of early

times, an important document among those commonly

available on the subject in English.

|

|

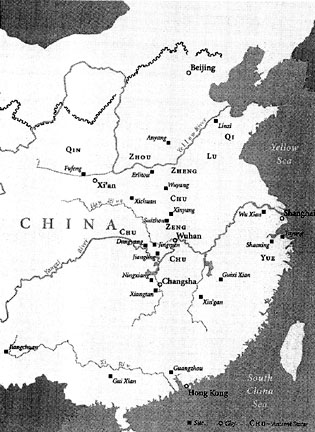

Map showing major sites, cities, and relative

locations ancient states,

From Music in the Age of Confucius,

page 115

|

Neolithic Period ca.7000- 2000 B.C.

Bronze Age ca.2000-500B.C.

Shang dynasty ca. 1600-1050 B.C.

Zhou dynasty 1050-221 B.C.

Western Zhou 1050-771 B.C.

Eastern Zhou 771-221 B.C.

Warring States Period 480-221 B.C.

Qin dynasty 221-206 B.C.

Han dynasty 206 B.C.-A.D. 220

Western Jin dynasty A.D. 265-316

Tang dynasty A.D. 618-907

Song dynasty A.D. 960-1279

Northern Song A.D. 960-1127

|

|

Five-stringed zhu-zither, with detail, from the

tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Leigudun,

Suizhou, Hubei Province. Fifth century B.C.

Carved lacquered wood. Length 115 cm, width

7 cm, depth 4 cm, Hubei Provincial Museum.

Photograph by Hao Qinjian.

|

|

|

detail.

|

In retrospect, the catalog and exhibit of " Music in

the Age of Confucius " constitute a vision of the

present state of ancient music.

Among the mysteries that

always multiply around

increased knowledge, they

provide us with as clear a view

as possible of what we now

know, and something of what

we do not know, about this

remote time; and especially, of

what we do not know about the

music itself. This is almost

certainly lost, forever reduced to

the written descriptions of its

sounds, instruments, and social

roles that still are found in

ancient texts, as well as to what

we may glean from the mute

peculiarities of its antique

artifacts. It is clear, however,

that music had an importance in

the world extreme beyond

anything like its place today.

Now, music reaches its deepest

significance inside the

solipsistic world of personal

experience, but anciently, up

through the Han at least, the

numerical relationships within

music were thought to embody

or reflect the natural essence of

the universe, including the

world of human experience.

Then, music harmonized the

world, just as, up to a few

centuries ago, the harmony of

the spheres regulated the

heavens of Europe. Today, what

we know of the old music from those who experienced

it is found in ancient reports like the Li Chi, or Record

of Ritual, which still reminds us of the meaning of

music and rites in distant times:

"Thus, music comes from within, and rites act from

without. Coming from within, music makes our minds

serene; acting from without, ritual makes our gestures

elegant. Yet, great music must be easy, and great rites, simple."

|