| |

Main Menu

Main Menu

選 項

Year 2000

Year 2001

Year 2002

Year 2003

| |

C.C. WANG DISCUSSES THE ART OF PAINTING

Date: 25 September 2000

Time: 2:00-4:30PM

Place: China Institute, 125 65th Street, New York City

Minutes: Matthew Flannery

Member Attending:

Stephen Dydo, Willow Hai Chang, Matthew Flannery, Shida Kuo, Yuan Jung-Ping

Events:

Alan has published an account of the

practice and role of retreat among the literati

aristocracy through the sixth century.

The particulars: Alan J. Berkowitz Patterns of Disengagement: The Practice and

Portrayal of Reclusion in Early Medieval China

Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000 296 pp., hardbound, $55.00 ISBN: 0-8047-3603.0

The book concerns the rationale, practice, and

portrayal of reclusion in China from the earliest

times through the sixth century, by which time

reclusion largely acquired its enduring character.

Essentially, the touchstone of the man in reclusion was

conduct and personal integrity that was manifested in

the unflinching eschewal of official position. It was his

outsider's stance that constituted the cause for public

acclaim of the recluse: men in reclusion forwent

opportunities for worldly success and a role in the

central government, but they did not surrender their

integrity nor compromise their resolve, mettle, or moral

and personal values in the face of adversity, threat, or

temptation. The book treats the practice of reclusion

and individual practitioners within the social, political,

intellectual, religious, and literary contexts of the times.

It also treats the topos ubiquitous in Chinese culture of

" the recluse, " who classically resided quiet and

unperturbed in his rustic dwelling amid a benign

wilderness.

Alan notes that little is said in his work of the

artistic, including musical, aspects of the recluse, and

adds that " I must make up for this great lapse in the

future.

The Meeting: C. C. Wang Discusses the

Art of Painting

|

|

Mr. C.C. Wang discusses the art of painting at the China Institute.

|

It centered on a discussion of Chinese painting by

Wang Ch'i-ch'ien 王己千(C. C. Wang). Mr. Wang is

equally noted for excelling in three fields related to

painting. He is a connoisseur of early painting

(especially, the Tang through Yuan periods, 960-1368),

a collector of paintings

from many periods, and a

landscape painter who

excels both at traditional

brushwork and at

extending that tradition

into new arenas. Beyond

painting, his calligraphy

is also sought and

collected.

In painting, he is

especially known for

basing the brushwork of

traditional landscape

painting on aleatoric

elements created by pretreating the paper. For

example, sometimes he impresses papers with inked

planks to create wood patterns, or he crumples them

into balls and dips their projecting angles into pooled

ink. The resulting lines, blots, and patterns are then

converted into landscapes by adding traditional

elements trees, huts, rocks, varieties of landscape

texture strokes in ink or color. To color such broad

areas as mountains and rivers or add sunsets, he usually

adds washes of light color.

|

|

Jung-Ping and Mr. C.C. Wang at the China Institute.

|

Mr, Wang, with occasional interpretation assistance

from his daughter Wang Xiange王嫻歌, began by

saying that an artist is not an expert on the academics of

painting but perhaps may contribute some idea of what

painting is about. After 50 or 60 years in the art, he has

learned that the viewpoint of those who do and do not

know about painting is slightly different. He noted that,

while the Qin Society is about music, painting is

nothing other than visual music.

The purpose of painting in its formative years was

to reproduce reality. This was generally true in east and

west: the formative steps of painting are to bring real

forms under the control of artistic tools. In the west,

however, reality long remained the principle criterion

by which the quality and social acceptability of painting

was judged. The aim was to capture the essence of a

thing by portraying its outward form as exactly as

possible. Even in the east, this was true of some

schools of painting, such as the academic or courtly

style that flourished under Hui-tsung 徽宗 (r. 1101-

1126) of the Northern Sung (960-1126). But in other

schools of eastern painting, there was less interest in

literal realism.

|

|

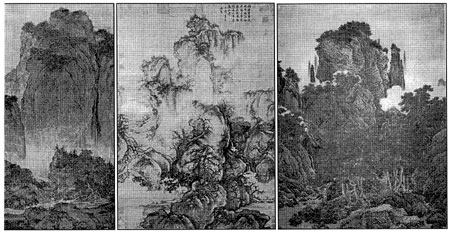

Fan Kuan 范寬(early eleventh century), Quo XI 郭熙(late eleventh century), and Li Tang 李唐(early twelfth century)

豀山行旅圖 Traveling among mountains and streams" 早春圖 "Early Spring" 萬壑松風圖 "Pine Winds in Ten Thousand Valleys"

|

Even as eastern art also strove for realism, it

modified this trend by the appreciation of calligraphy

and music for the abstract line, and, even as painting

remained fundamentally based in realism, abstraction

became one of its important values. Eastern painting,

he noted, was like opera: its sets, shallow acting space,

and distinctive singing style were suggestive of reality

without replicating it exactly, while western painting

was more like drama, with its often more realistic sets

and spoken lines. While east and west began from the

viewpoint of realism, by the Northern Sung, the

abstraction of calligraphy becomes observable in

eastern painting, whereas western painting did not

begin to investigate this approach until the nineteenth

century.

Eastern figure painting before the Tang did not

reach the technical perfection eventually achieved in

the classical ancient west, but the linear, calligraphic

expression of its linework was sufficient to capture

emotional expression of a figure. With line important,

so the brush was important. East and west, brushes and

strokework were different. In eastern painting,

brushwork became the criterion for judging the quality

of a painting, for distinguishing between good and bad

painting as well as authentic and inauthentic paintings.

If one can distinguish the type and style of brushwork,

one can determine the authenticity of a painting based

on its brushwork. Western paintings are more heavily

worked over, with paint added in layers, which makes

the brushwork more difficult to analyze. In eastern

painting, where strokes are laid down individually with

little correction or overpainting, strokes stand clear

before the connoisseur's eye, making it relatively easy

to authenticate a painting.

|

|

Ni Can, 倪瓚(1301 -1374)

The Rung Xi Studio 容膝齋(1372)

|

Mr. Wang said he is frequently approached by

westerners regarding his opinion of the authenticity of a

painting. Still, they wonder how he can authenticate a

painting while they cannot and tend to lose confidence

in his judgment. The key is that one must do painting

to understand it. Looking at a painting is like going to

the opera: one must listen to the vocal quality, not just

the storyline. That is how anyone can tell, just from a

" Hello, " who is speaking if they know that person

well. And if faking a single "hello " is easy, it is

much harder to fake an entire conversation or a

painting.

Chinese art theory is that great artists have greater

characters, and hence they have the more distinctive

styles. Ni Can's 倪瓚(1301-1374) work, for example,

is so simple, yet it says everything. A rock, a tree, and

a hut are all that is needed to express one's ideas,

emotions, talent. A painting is a reflection of an artist:

it sings his song. If his work looks too much like that

of others, then the individual is not a great artist.

Hence, Mr. Wang concluded, it is this distinctiveness,

especially among great artists, that allows their work to

be judged and authenticated by connoisseurs.

|

|

Mr. Wang replied that musical sounds can describe a

brook or a bird, as can the brushstrokes of a painting......

Wang Xiange (right)

|

Those attending had some questions. Stephen

noted that painting, like calligraphy, includes a time

element in the process of painting, the path of the

brush. Is this what Mr. Wang meant by the relationship

between music and painting? Mr. Wang replied that

musical sounds can describe a brook or a bird, as can

the brushstrokes of a painting. But the abstract

qualities of music are like those of painting, and these

are the heart of the matter. A bird and a brook, a rock

and a tree do not mean anything:

they are the vehicle for the

abstract expression of the

brushwork. An artist does not

describe a mountain. He

describes its beauty and spirit.

Western abstraction is so obvious

that it is easily seen, but in the

east it is harder to detect it hides

behind the things it describes, just

as, in calligraphy, the brushwork

hides behind a calligraphy's

literary message, which tends to

distract its viewers from its

graphic qualities. But it is

precisely in the abstract quality of

the brushwork that the essence

and value of painting and

calligraphy reside.

|

|

Hui-tsung 徽宗(r. 1101-1126) "Listening to the Qin."聽琴圖

|

Jung-Ping asked whether the

three scrolls that Mr. Wang had

had hung across the wall of the

room represented different

schools of painting. Mr. Wang

replied that all three were

reproductions of Northern Sung

paintings by different artists and

did so much not represent

different schools as the different personal styles of their

three artists, styles that eventually became models for

later artists. The three artists represented. Fan Kuan 范寬(early eleventh century), Guo Xi 郭熙(late eleventh

century), and Li Tang 李唐(early twelfth century), all

used variations in brushwork to express their various

personalities. Hence, all three scrolls show painted

mountains with their own personalities, mountains that

look neither real nor like each other.

|

|

Stephen played "Ping Sha Lo Yen" ("Wild Geese Descending to Sandy Shores").

|

Qin Performance:

After Mr. Wang's talk, Stephen played "Ping

Shao Lo Yan" 平沙落雁( "Wild Geese

Descending to Sandy Shores"). "Ping

Shao Lo Yan" is extant in more than 30 variants which

usually have five, seven, or ten sections. Its earliest

score is found in the qin manual Gu Yin Zheng Zong

古音正宗(1634).

Jung-Ping then played two pieces, "Mei Hua San

Nung" 梅花三弄(" Three Variations on the Plum

Blossoms o") and "Pu 'an Zho" 普庵咒("Chant of

Pu'an"). Of the two themes in "Mei Hua San

Nung," the first is repeated three times in successively

higher registers; hence the title. Said to date in its

original form from the Qin and Sui dynasties, it was

arranged for qin in the Tang by Yan Shigu 顏師古.

"Pu'an Zho" is first found in the San Jiao Tong Sheng

Pu 三教同聲 of 1592. It purports to record a chant by

Pu'an, a Buddhist monk.

Members: Alex Chao, Stephen Dydo, Matthew Flannery, Willow Hai, Shida Kuo, Bo Lawergren, Gopal Sukhu, Yuan Jung-Ping

|