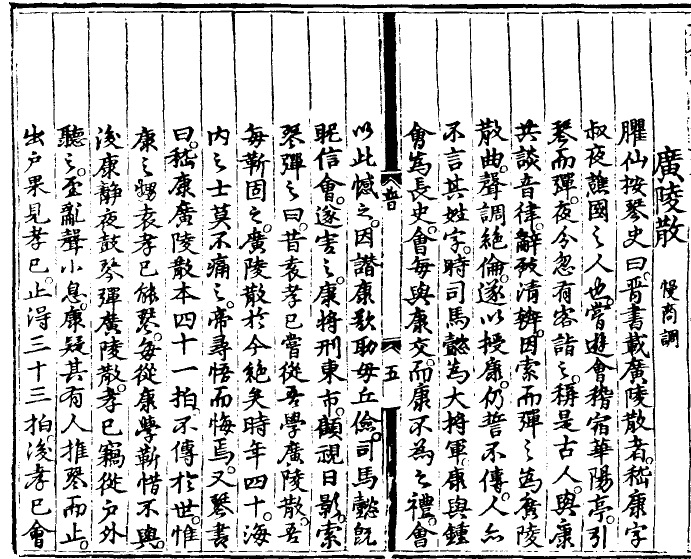

廣陵散打譜

On Sunday June 12, 2022, 3pm EDT, the following members and a guest from LYQS presented different versions of Guang Ling San :

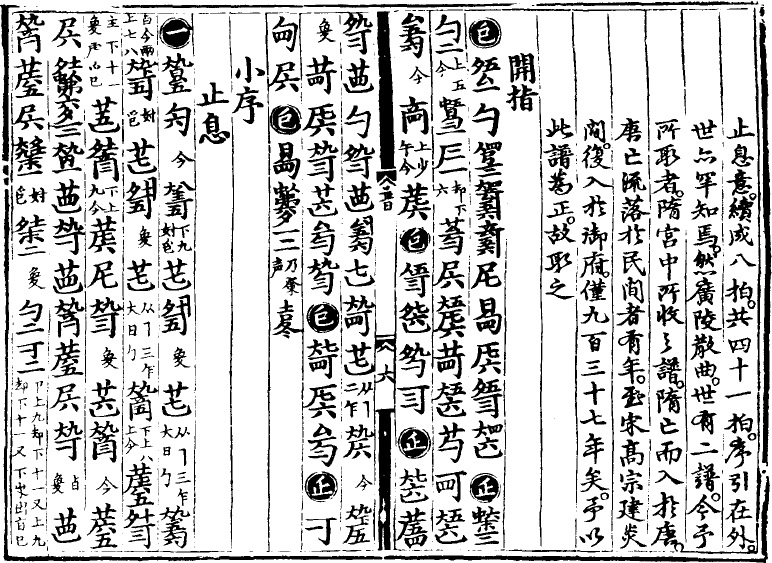

1, John Thompson 唐世璋 – 神奇秘譜 SQMP (明 1425) ( 1:30 )

For better sound quality, please listen John’s performance from this link:

http://www.silkqin.com/06see/videosJT/zoomNYQS/GLS4NYQS.mp4

On 7/14/2022 John wrote:

I have posted my own transcription and recording of the Guangling San published in Guyin Zhengzong (1634)

http://www.silkqin.com/02qnpu/41gyzz/gy5960gl.htm

in particular

http://www.silkqin.com/02qnpu/41gyzz/gy5960gl.htm#music

It is quite different from the interpretation by Li Youxin, but you can use my transcription to perhaps more easily follow Li Youxin’s interpretation.

From the various original commentaries (which I have linked to that commentary) as well as my own it is clear that this latter Guangling San has nothing to do with Nie Zheng Story and the earlier theme.

On my transcriptions I point out how the Guyin Zhengzong is related to the next one, from 1802, which version is almost the same as the Shiyixianguan Qinu version. So you could also use that if you listen again to Julian’s recording (or to the one by Chen Changlin which I have linked here:

http://www.silkqin.com/02qnpu/07sqmp/sq02gls.htm#1907b

2, Juni Yeung 楊雪亭 – 西麓堂琴統 XLTQT (明 1525) ( 1:02:02 )

3, Peiyou Chang 張培幼 – 古音正宗 Gu Yin Zheng Zong (明 1634) and a silk string qin recording from Mr. Li You Xin 李佑心絲絃演奏錄音 ( 1:24:51 )

You can also listen Mr. Li You Xin 李佑心絲絃演奏錄音 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6sh6eT259A

And Peiyou’s playing of 古音正宗 廣陵真趣:

https://youtu.be/RkHg1xRN6qQ

4, Guest, Julian Joseph – 十一絃館琴譜 Shi Yi Xian Guan Qin Pu (清 1907) ( 1:59:46 )

5, Mingmei Yip 葉明媚 – Commenter ( 2:22:10 )

Attendance

Alan Yip, Esmie(Ana Herrero), John Thompson, Juni Yeung, Lawrence Kaster, Andre Lioy, Mandy Szostek, Marilyn Wong Gleysteen, Peiyou Chang, Mingmei Yip, Matthew Flannery, Lisa Raphals, Andreia Alves, Charles Tsua, Julian Joseph, Andre Riberiro, Bin Li, Jane Huang, Joao Oliverira, Yanchen Zhang, Zhaojin Ji, Ana Trajano, Ralph Knag, and Char Chi Teng 鄧家齊

Q&A

There are some questions from a new friend, Char Chi Tang 鄧家齊 (who wrote 嵇康·《广陵散》及其他 and shared his composition of a Cantonese music 珠水雲霞) to the yaji:

我希望能夠通過講座向各位老師請教的是:一,古琴有七弦,按宮、商、角、徵、羽定音,而且演奏方法有「正弄」和「側弄」之分。什麼叫「正弄」、「側弄」?能否請老師在講座中展示一下?二,《廣陵散》一曲採用了特別的「慢商調」弦式,需要把二弦降低大二度與一弦同音。後世有觀點認為該曲二弦(臣)與一弦(君)同,成「凌君」之態,屬大逆不道,這也是後世儒家學者對《廣陵散》持非議態度的重要原因。現在經打譜之後,彈奏《廣陵散》時還是否需要把古琴的二弦調低與一弦相同?三,《廣陵散》出自漢晉時期,明代的《神奇秘譜》以減字譜發佈該曲曲譜。這樣看來,《廣陵散》應該屬於中國古代清樂或者燕樂範圍。而中國古樂與現代使用十二平均律的五線譜或簡譜在音高和音準方面是有差別的,在《廣陵散》打譜之後,《廣陵散》古譜與現代樂譜的差距是如何調整的?謝謝各位老師!

鄧家齊

Answer for Char Chi’s question 1, 2 and 3 from Juni, Peiyou and John by June 11:

I’ll be responding in text (WHILE AT WORK), in English here for everyone to see:一,古琴有七弦,按宮、商、角、徵、羽定音,而且演奏方法有「正弄」和「側弄」之分。什麼叫「正弄」、「側弄」?能否請老師在講座中展示一下?

Q1. “The Guqin has 7 strings, set pentatonically with Gong/shang/jue/zhi/yu. Also, it can be played with something known as “zhengnong” (proper playing) and “cenong” (side transposition). Can any teacher explain what that means?

A: The qin’s seven strings are always set to one tuning or another, orthodoxically something we call “standard tuning”. Any given tuning (ie. a set of coherent pitches) (diao 調) can be recognized with certain modes (also referred to as diao 調) based on certain fundamental tones (yun 均, note the special reading same as 韻). “Proper transposition” is if you play said tuning in the modal quality it comes preconfigured in as-is, using its assumed starting tone (gong) on a certain string, the relationships with other strings, so forth. “Side transposition” is if you use a said same tuning but intentionally reposition/repurpose said tuned strings to be interpreted differently, for example instead of treating Str.III as gong on standard tuning, you intentionally avoid some tones (eg. 10.8@III) and play a piece that uses Str.I as gong. What you’d be doing is transposing up or down a given piece of music (the “software”) to be performed from a different position on the instrument (the “hardware)”.

Standard Tuning offers the most variation in this respect, with 5 variations of internal “side transpositions” – they are known as the neidiao 內調. If you have to start tuning strings physically to achieve a different modal flavor, that’s waidiao 外調 “external tuning”, which comes in two categories – perfect and imperfect transitions. Each of these external tunings usually offer 1 or 2 ways to be understood, so those can be internally transposed as well.

I’ll leave the other questions to others. *kicks the ballfor a pass*

藝工琴棋好生無量天尊﹗ Juni L. Yeung, MA (Toronto)

Q2. The song “Guangling San” adopts a special “man shang” mode, which requires the second string to be lowered by a major second to be in tune with the first string. In later generations, there are views that this lower the 2nd string (which represent the minister) to match the 1st string (which represent the monarch) is in the same state as “insult the monarch”, which is a great rebellion. This is also an important reason for later Confucian scholars to criticize the “Guangling San”. Now, after playing the score, do you still need to lower the second string of the guqin to the same level as the first string when playing “Guangling San”?

My response to this question is that there are musicality reasons to keep the 1st and 2nd string same tone.

如果不考慮儒家思想, 僅就音樂性來說,一二絃同音有其目的, 以下三文中有其解釋: 1. 丁承運先生提到的”《广陵散》更是把三种音色对比做到极致的典范,它的妙处在于降低二弦与最低音的一弦同音,最大限度地加强了低音浑厚的音效与张力.” (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vhDVEUI2NUwSP0wZwfxN6Q) 2. 王世襄先生在其文章[古琴名曲廣陵散]中說的”廣陵散的定絃法是一二兩絃同音高, 這兩絃同時打撥, 加重了主音的音量…使氣氛非常緊張”. 3. 王迪與齊毓怡合寫的[琴曲廣陵散初探]中認為”同音重疊模擬擊鼓聲”

If you don’t consider Confucianism, just in terms of musicality, it is explained in the following three articles: 1. The “Guangling San” mentioned by Mr. Ding Chengyun is a model of the extreme contrast between the three timbres (open, pressing and harmonic). Its beauty is that It is to lower the second string and the first string of the lowest note, which maximizes the sound and tension of the bass.” (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vhDVEUI2NUwSP0wZwfxN6Q)

2. Mr. Wang Shixiang said in his article [Guqin Famous Song Guangling San] that “making the 1st and 2nd string to the same pitch, and playing together, increasing the volume of the main voice…making the atmosphere very tense”. 3. Wang Di and Qi Yuyi co-written [Qin Song Guangling San] mentioned “Unison overlap to simulate drumming.” — Peiyou Chang

Q3. My understanding of the third question that “maybe I can answer” is “I cannot answer”, I can only point out a few things from my understanding.

“Guangling San” comes from the Han and Jin Dynasties, and the “Shen Qi Mi Pu” in 1425 CE published the melody in simplified tablature. From this point of view, “Guangling San” should belong to the scope of ancient Chinese 清樂 or 燕樂. However, there are differences in pitch and intonation between ancient Chinese music and modern notation or musical notation using twelve equal temperaments. After dapu “Guangling San”, how to adjust the gap between the ancient score of “Guangling San” and the modern staff notation score?

First there is no hard evidence that the melody as published in 1425 is connected in any way to whatever melody was played in the time of Xi Kang, or the melodies with that title before him. From my understanding, a good argument can be made that the 1425 Guangling San was copied from Song dynasty tablature, maybe as early as the 10th century, but even this is speculation. The fact is that a number of surviving melody titles have completely different forms from published earlier versions. Why not the same with Guangling San. (This is also my understanding of what 丁承運 Ding Chengyun wrote.)

Second, although there is evidence of people in ancient time trying to find the perfect pitch of a 黃鐘 Yellow Bell, to my knowledge this changed a lot, was never recorded in a way that we understand today (no way of measuring vibrations per second), and no one knows how this was connected to music people played. Specifically for guqin, no one knows to what pitch any string of any qin before the 20th century was tuned to. In this, Chinese music is similar to most Western music before the end of the 19th century.

Please let me know if I misunderstood the question, or if my understanding of the answer seems wrong.

John

Mingmei, May I ask whether Guangling San was among the pieces you learned from Mme. Cai Deyun? From Messers Benny Shum and Sou Sitai I understand that 瀟湘水雲 was the most “advanced” piece that one would learn with her.

I am now listening to Wu Wenguang’s version of Guangling. From his interpretation, it sounds like a virtuostic impressive piece to show off one’s qin technique. I would have trouble imagining it as the final piece before a qin master’s death, but perhaps the fast tempo is supposed to arouse heightened emotion in the listener, and not necessarily in the player. What do you think? I hope Peiyou and others discuss some of the interpretations. ML

Mariyln, The most advanced piece taught by my teacher is this one and 胡笳十八拍。

”it sounds like a virtuostic impressive piece to show off one’s qin technique. I would have trouble imagining it as the final piece before a qin master’s death“

I think that it makes sense as a final piece before one’s death, for he must be very angry and agitated — both for his own impending death and Nie Zheng’s death. Of course on the other hand he could also play it rather “calmly” (accepting his fate, but I doubt that) like Guan Pinghu’s interpretation. But judging from the composition’s structure, some sections should be played with “showy” technique, agitation, and with the hand flying out. This piece is a breath of fresh air in the qin repertoire!

Mingmei

Documentation: Peiyou Chang